There are often misalignments in the available time for a project implementation and the full range of work that needs to occur. As a technical project manager, I have managed this scenario many times as a result of optimistic sales schedules, distorted expectations of the custom software implementation (versus installation of out of the box software) or a variety of other reasons.

Kenneth Darter wrote in a in March 3, 2014 blog post on ProjectManagement.com that there are 3 Methods to Managing Customer Expectations: Optimistic, Realist and Pessimistic. Different organizational groups lean towards different methods. An optimistic approach can result in customer & team frustration when hiccups or schedule slippage occurs, while pessimistic approaches sometimes breed mistrust as the estimates are so padded that nobody believes them. Realism in project estimation requires significant a solid understanding of the team players, the work that needs to happen & client expectations.

https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/understanding-the-project-management-triple-constraint.php

https://www.projectsmart.co.uk/understanding-the-project-management-triple-constraint.php

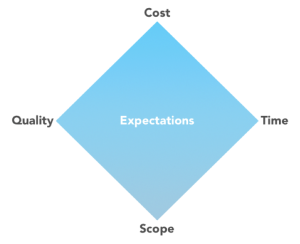

As Duncan Haughey pointed out in his December 19, 2011 post on Project Smart, it is often said that there is a 3-way constraint In all projects between cost, time and scope, with quality assumed. This has recently evolved to a 4-way diamond of cost, time, scope, quality, with customer expectations as the foundation. Without understanding the customer expectations, it will be incredibly difficult to you make the right decisions regarding cost, time, scope or quality.

Regardless of your primary method for setting schedules, you will always need to take into consideration cost, time, scope, quality, and most importantly customer expectations.

- Communicate the Facts – In reviewing the list of work before a weekend migration project, it became apparent that there were more machine hours of work to migrate some historical data than existed in the weekend of the deployment. Armed with the facts, I was able to talk the client into reducing the scope of the historical data migration for the deployment weekend and plan for remaining work after the fact.

- Discover the Business Motivation – During a data integration project with aggressive timelines, a client requested 2 weeks for internal validation. After initial pushback, it became apparent that the issue wasn’t our work, the client had data quality concerns from the source and needed to determine the impact to the business. We were able to tweak our approach to the project to help mitigate some of the concerns.

- Be Vigilant – As a project manager it is imperative to keep your pulse on the project. When snags occur (and they will), you need to communicate loudly and often to ensure the project team and the client understand what happened, why it happened and how it’s being resolved.

At the heart of every project are the client expectations. While there is an inherent quality you should push your project team towards, cost, scope & time will all radiant around the expectations and adjust as required.

Dagny is currently Managing Director at Digital Ambit, a consulting company focused on helping you with your data and software integration needs. Dagny has almost 20 years of experience in project delivery & customer success of software implementation projects.

Dagny is currently Managing Director at Digital Ambit, a consulting company focused on helping you with your data and software integration needs. Dagny has almost 20 years of experience in project delivery & customer success of software implementation projects.